"In the misty Himalayan hills, where the river greets the sun,

The mountains, like a mother, guided it in every run.

Through rocky paths and hidden streams,

It watched its destiny in gleams.

But today there stands someone tall,

Giving hope and courage to achieve it all."

Today, the river reaches a point where it must bid farewell to its mountain friends. One journey ends, and another begins, as it flows beneath someone mighty and great. More than just a structure, it stands as a guardian, a guide, and a symbol of strength, a lifeline for countless lives across generations.

One that has stood unwavering through time, and will be remembered for ages. Today, we pay tribute to this ever-standing structure — the epitome of engineering excellence and resilience: the Coronation Bridge, fondly called Bagh Pool.

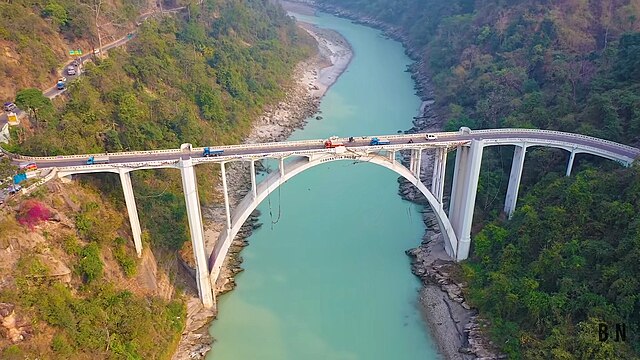

Coronation Bridge Drone View Wikimedia Commons

History

This story begins at a time when the world was full of tension and conflict. In the East, Japan was preparing to invade China to expand its empire. In the West, Germany was attacking nearby countries under fascist rule. Meanwhile, in South Asia, India remained under British control, and the freedom movement continued to grow stronger. Around this time, the first provincial elections were held under the Government of India Act of 1935, and the Indian National Congress won most of the seats.

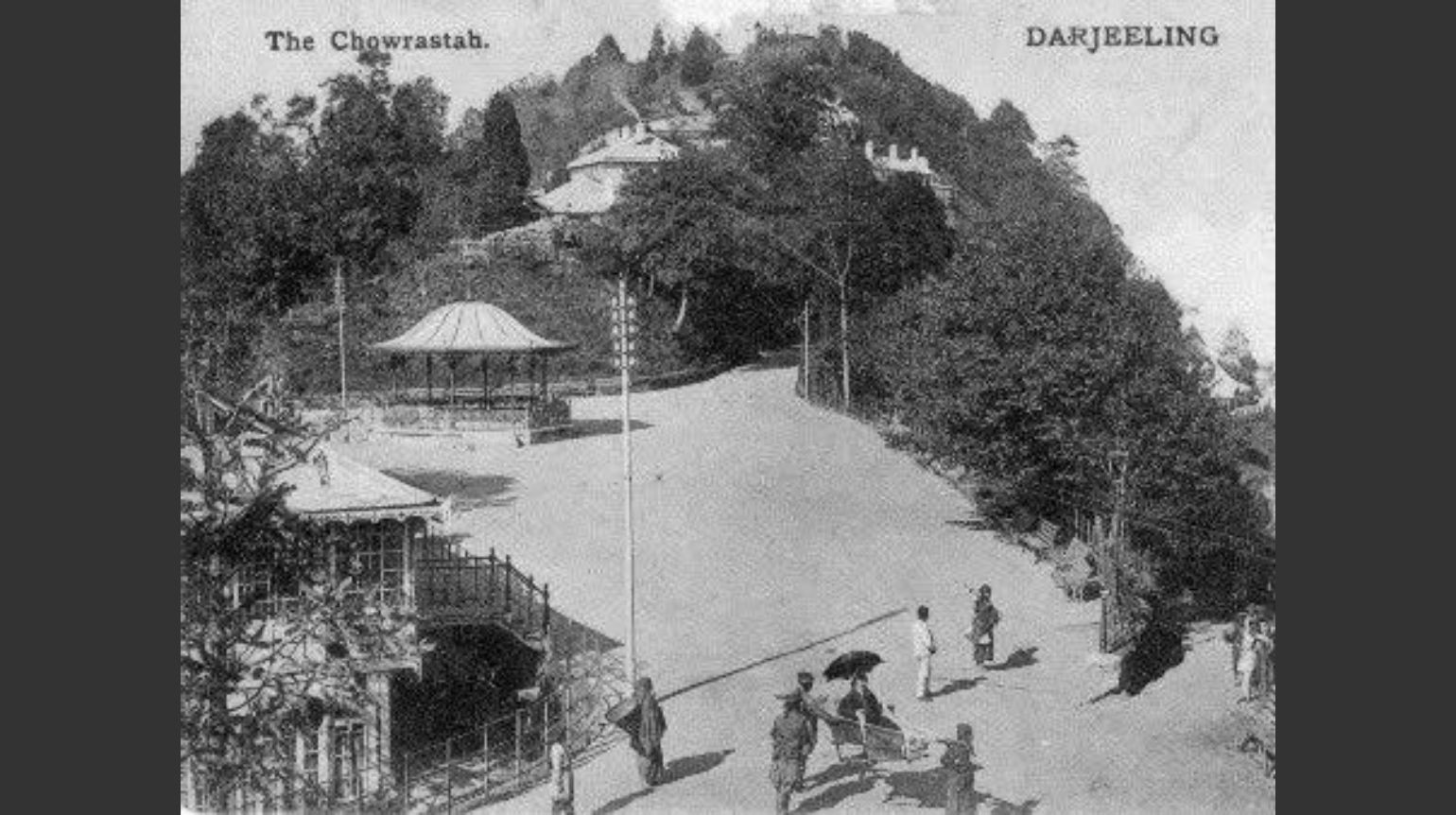

During this time, British-led agriculture and tea farming in India were thriving. Tea plantations, especially in Assam, Darjeeling, and the Western Ghats, had grown into a well-developed industry managed by the British.

Established in the early 1800s, these plantations transformed India into one of the world’s largest tea producers. By the late 1930s, tea had become an important part of India’s economy and a valuable asset for the British Empire.

In the Dooars region, which connects India to Bhutan, the growth of tea farming brought big social and economic changes. The area was home to local tribes like the Koch-Rajbanshis, Mech, Garo, Toto, and Rabha, but it wasn’t densely populated. When the British started expanding tea gardens in the late 1800s, many locals were not interested in working as laborers. To solve this, the British brought workers from the Chhotanagpur plateau, including tribal groups such as the Oraons, Santals, Malpaharias, Kharias, Mundas, Lohars, and Mahalis.

As the tea plantations expanded, people from different groups—two tribal communities, Rajbanshis, Bengalis, Nepalese, and others—kept coming in, creating a mix of cultures and complex social dynamics. This put pressure on land, labor, and local communities. The British had to balance expanding farmland, ensuring enough workers, resettling locals and migrants, and keeping the economy stable. These changes also highlighted the need for better roads and transport in the region.

Seeing this, the British government decided to build a bridge to connect Darjeeling, the Bhutan foothills, the Northeast, and the Dooars with the Jalpaiguri plains.

The bridge was meant not only to improve trade and transport but also to help military and administrative movement across the region. To mark the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, the British commissioned the construction of a bridge over the Teesta River.

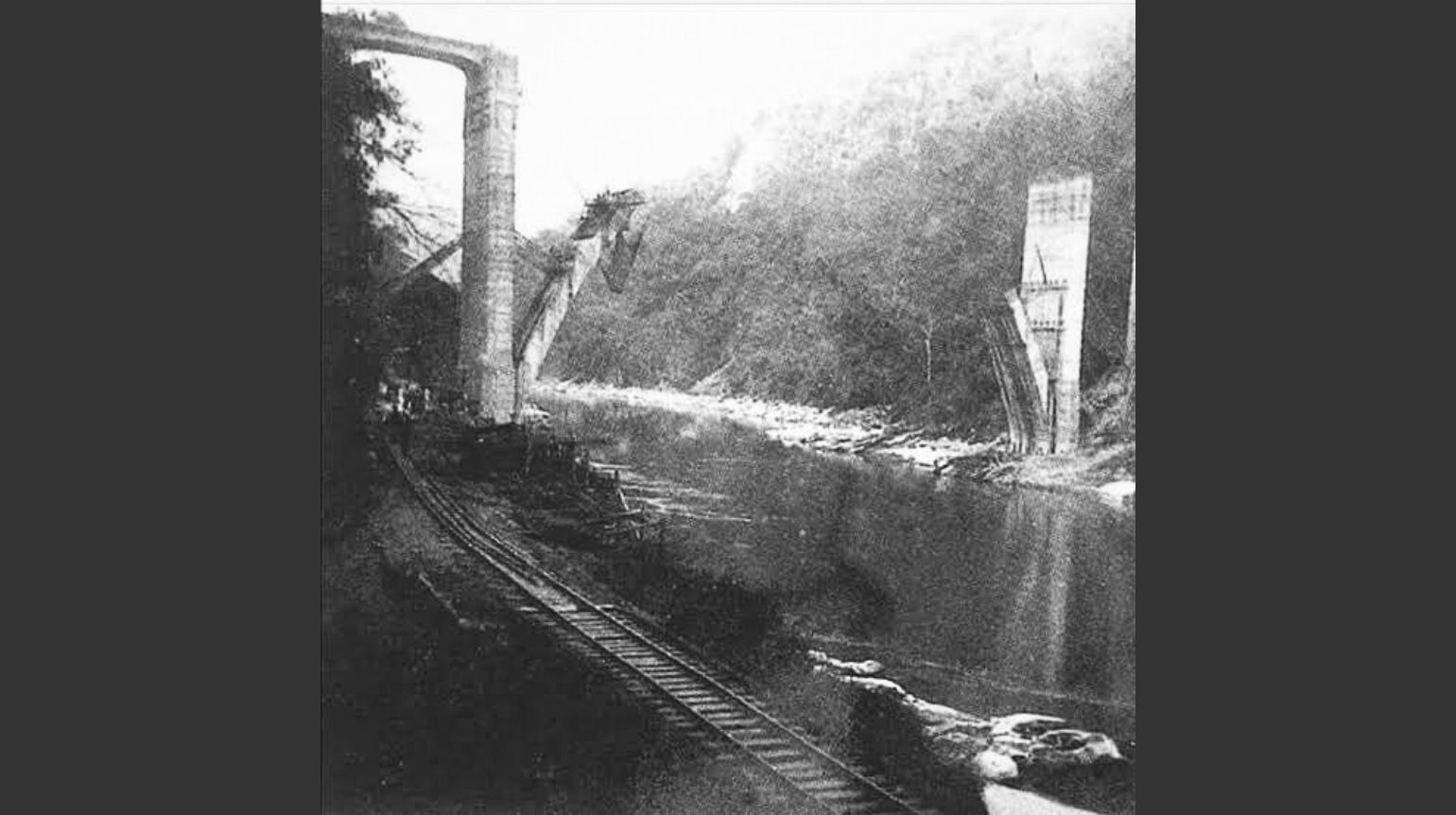

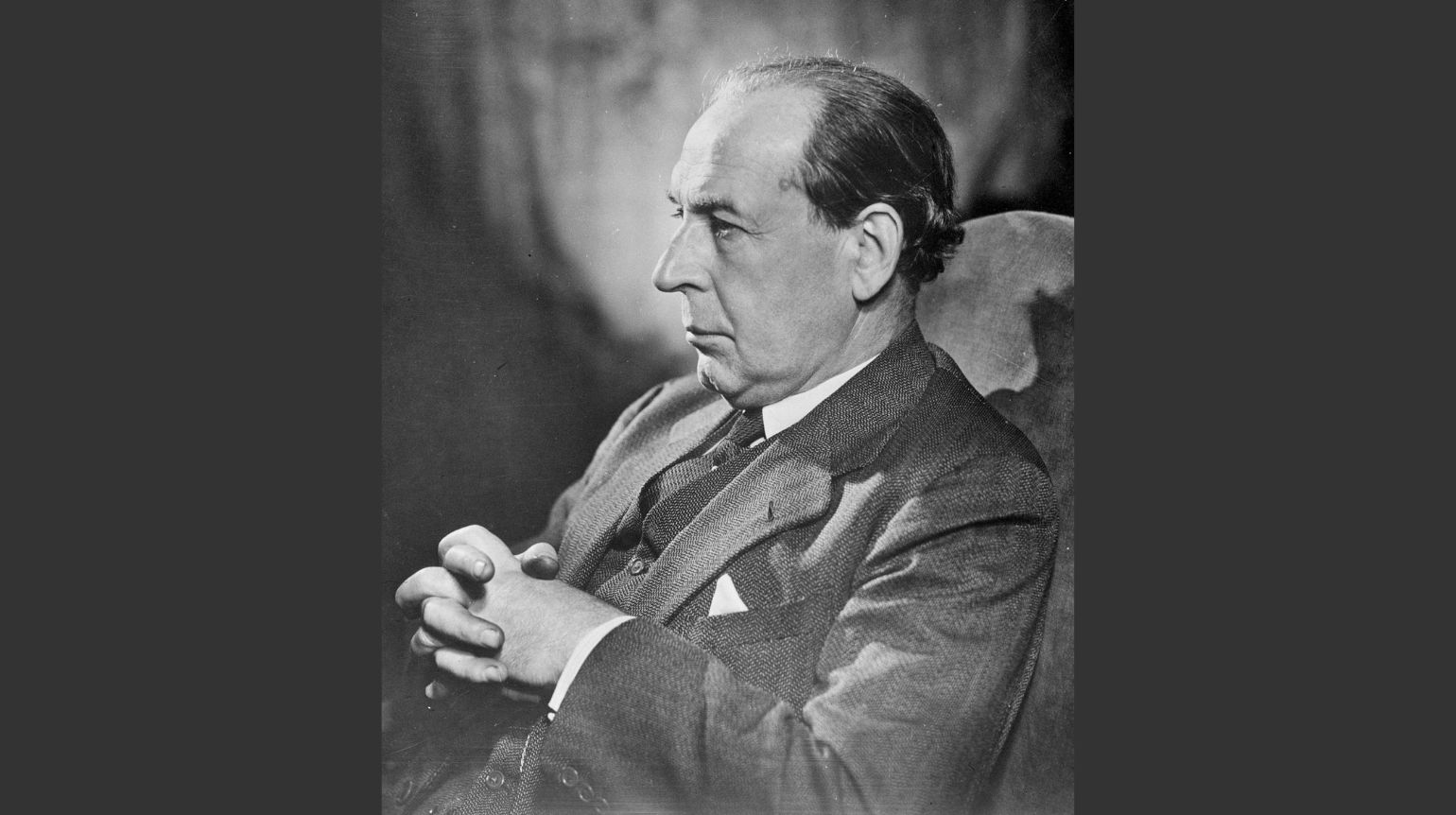

The foundation stone was laid in 1937 by John Anderson, then Governor of Bengal. The design was carried out by Bengali architects A.C. Dutt, S.K. Ghosh, and K.P. Roy, under the supervision of John Chambers, the last British Executive Engineer of the Darjeeling PWD.

This historic collaboration and engineering effort laid the foundation for what would become a vital link in the region, shaping trade, travel, and the socio-economic landscape for decades to come.

John Anderson

Design & Development

The Coronation Bridge is more than just an engineering achievement; it stands as a symbol of resilience and architectural brilliance built under some of the toughest geographical conditions. Construction began in 1937 and was completed in 1941 at a cost of around ₹6 lakh, which would be about ₹20.4 crore (US $2.3 million) in October 2025, after accounting for inflation.

The bridge was designed to create a vital link between the plains of West Bengal and the lush, hilly regions of the Northeast. Crossing the fast-flowing and turbulent Teesta River was no small task—many early attempts were considered impossible due to the river’s depth and strong currents.

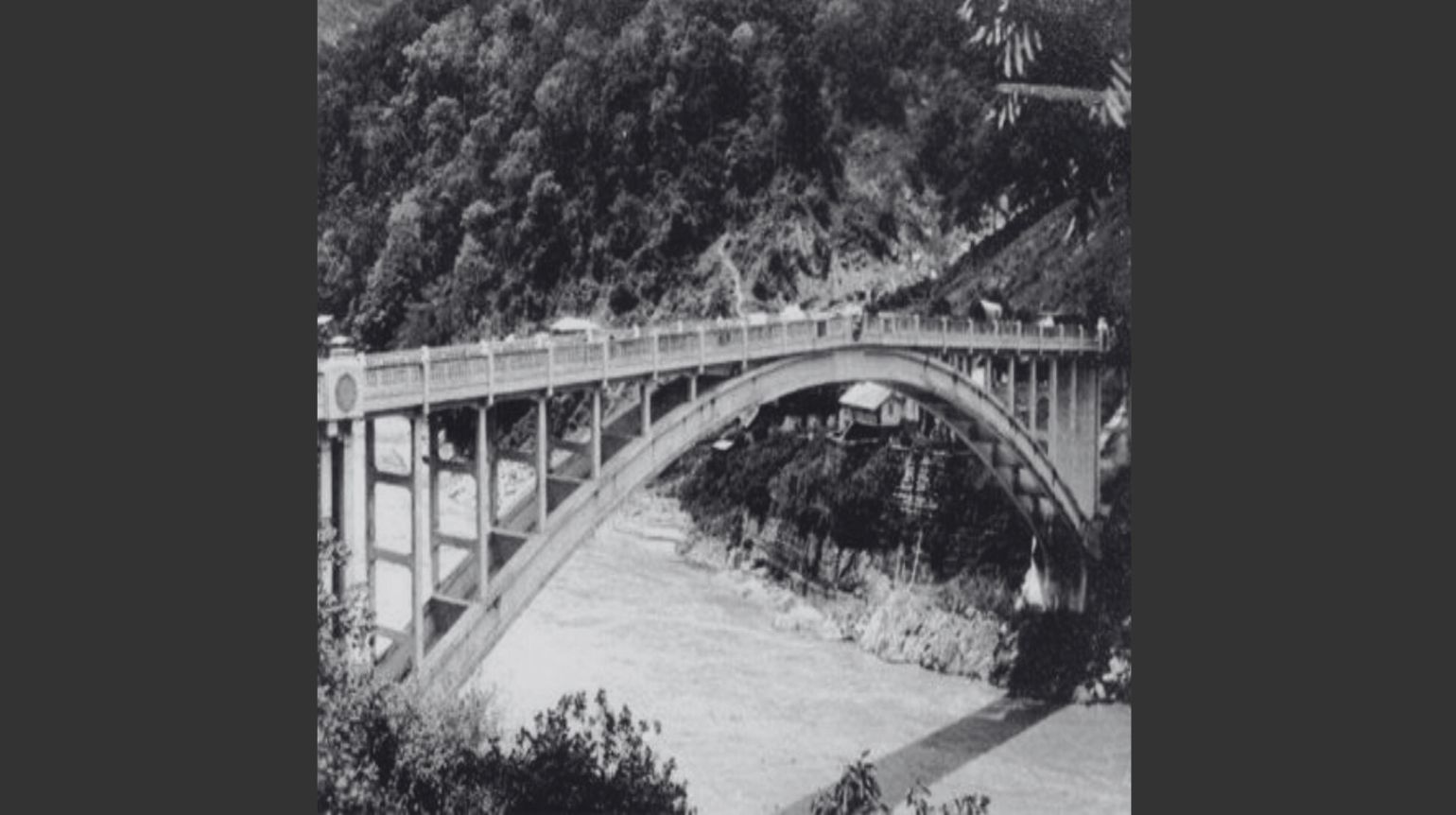

Coronation Bridge Ground View | Wikimedia Commons

The brilliance of the engineers is clear in their choice of a spandrel-arch design, inspired by ancient Roman architecture. Unlike usual suspension or truss bridges, the Coronation Bridge stands on a fixed arch anchored deep into the solid rock on either side of the Teesta River. This clever design transfers the river’s immense force directly into the rock, making the bridge both strong and long-lasting. The result is a graceful arch that seems to effortlessly span the gorge, combining elegance with strength.

What makes the bridge even more remarkable is the time in which it was built. The late 1930s were a turbulent period globally, with World War II on the horizon and resources running low. Despite these challenges, the British government went ahead with the project, seeing it as vital for military and administrative movement in the northeast. Today, the bridge stands as a testament to the vision and skill of its engineers.

The Coronation Bridge also carries deep cultural significance. Named to honor the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in 1937, it features two majestic tiger statues at its Jalpaiguri entrance. Locally called “Bagh Pool” or Tiger Bridge, these statues symbolize strength, guardianship, and resilience, silently watching over travelers and the passing of time

Over the years, the bridge has become more than a passage across the Teesta—it is a heritage landmark. Its bright pink color, added during later maintenance, makes it stand out against the lush green hills of the Dooars. Visitors often stop here, not just to admire the structure, but also to enjoy sweeping views of the Teesta River winding through the forests.

As modernization and new highways reshape the region, there are growing calls to officially recognize the Coronation Bridge as a heritage site. Such a step would protect its architectural and historical legacy, ensuring that this rare Roman-inspired spandrel-arch bridge continues to inspire awe.

The Coronation Bridge remains a living symbol of human ingenuity meeting nature’s challenges, an enduring monument of history, architecture, and culture in North Bengal.

Legacy and Cultural Significance

The Coronation Bridge is not just an engineering wonder of its time—it is also a cultural icon deeply connected to the identity of North Bengal. Acting as a key gateway between the Himalayan foothills and the fertile Dooars plains, the bridge has been more than a road—it has been a lifeline for trade, tourism, and cultural exchange for almost a century.

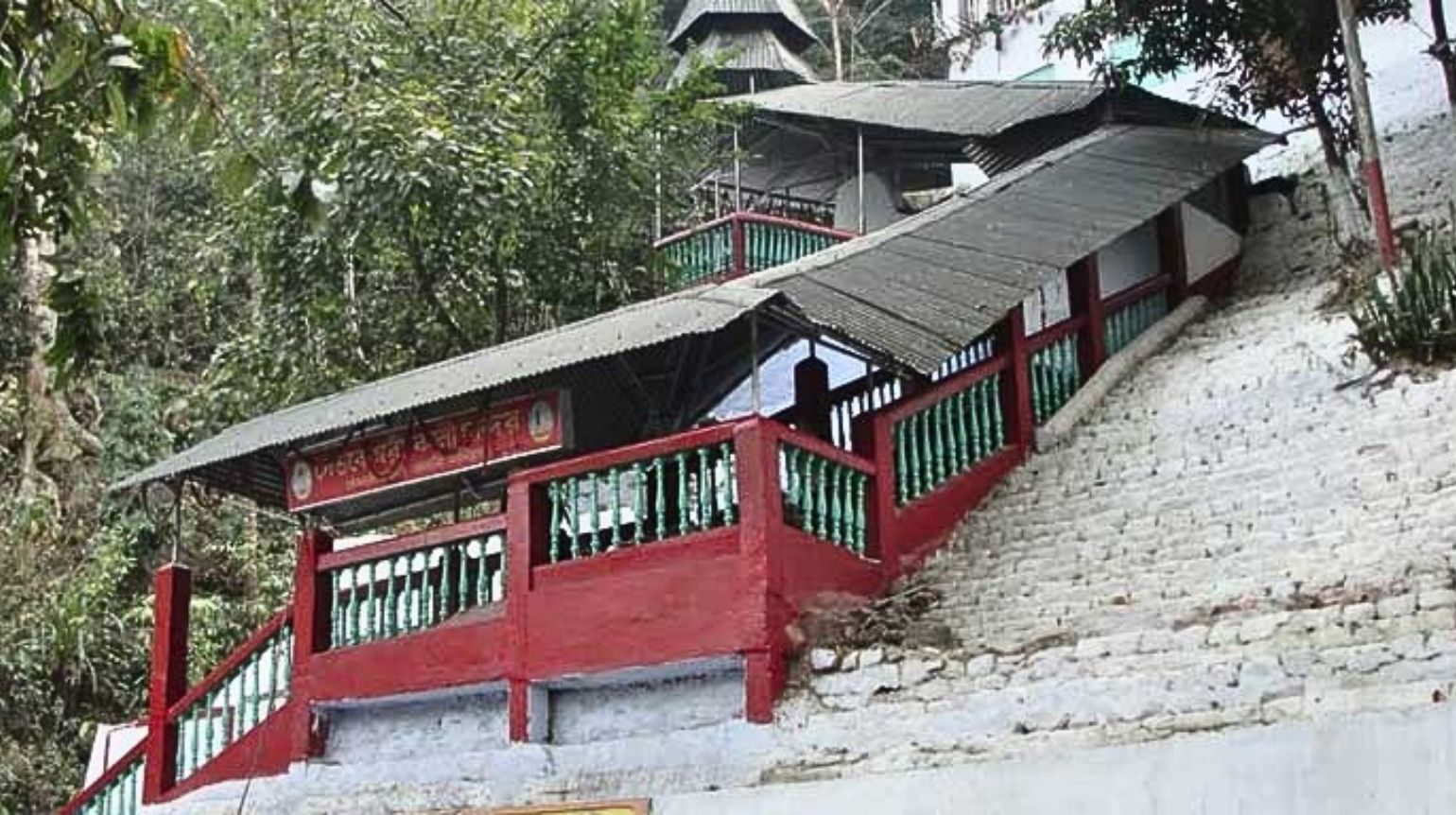

Its bright colors, set against the lush green forests and the turquoise waters of the Teesta River, make it one of the most photographed landmarks in the region. Nearby is the Sevokeshwari Kali Mandir, a revered temple perched on a cliff overlooking the river. Travelers and pilgrims often stop at the bridge not only to enjoy the scenic beauty but also to pay their respects at the temple, blending faith, history, and engineering in one spot.

Sevokeshwari Kali Mandir

Beyond tourism and religion, the Coronation Bridge holds a special place in regional pride. Being one of India’s last surviving spandrel-arch bridges, its design traces back to ancient Roman engineering, making it a rare architectural treasure. Heritage experts and engineers have long called for its recognition as a protected monument, highlighting its historical importance, beauty, and role in connecting Eastern India.

Damage and Ageing

Even though the Coronation Bridge was an engineering marvel of its time, years of wear and tear, natural disasters, and growing traffic have taken their toll. Built in 1941 with an expected life of about 100 years, the bridge has now served for over 75 years, making its maintenance a big challenge.

One of the earliest threats came from the region’s frequent earthquakes. In 2011, a 6.9-magnitude quake shook North Bengal and Sikkim, causing visible cracks in the bridge. While temporary repairs were done by the West Bengal PWD, engineers warned that ongoing tremors and vibrations from daily traffic continued to strain its fixed-arch foundation.

The Teesta River, fed by monsoon rains, poses another risk. Its strong currents and frequent floods have gradually worn away the rock banks where the arch is anchored. Rising water levels during cloudbursts and dam releases make the structure even more vulnerable.

Regular inspections over the years have revealed growing cracks in the arch and deck. In 2020, engineers from Jadavpur University reported a 2.5-foot crack in the arch. As a result, authorities imposed strict weight limits, barring heavy vehicles above 10 tons and forcing goods trucks to take longer alternative routes.

Traffic pressure has further accelerated the bridge’s ageing. Originally built for light colonial-era vehicles, today it carries thousands of cars, buses, and commercial trucks daily—far beyond its design. This constant load has caused visible wear on steel girders, concrete surfaces, and even ornamental features like the fading tiger statues.

Despite regular maintenance, experts warn that patchwork repairs alone are not enough. Without a parallel bridge to share the traffic load, the Coronation Bridge remains under severe stress. Its deteriorating condition has sparked repeated calls from engineers, politicians, and heritage groups to preserve it as a historical monument while building a modern bridge for heavy vehicles.

Plans for a New Bridge

The need for a new bridge over the Teesta River has been recognized for several years. Back in 2021, the Centre had approved ₹1,000 crore for constructing a second road bridge at Sevoke, running parallel to the existing rail bridge. This bridge was planned to link Darjeeling, Kalimpong, Sikkim, and the Dooars, providing an alternative to the iconic Coronation Bridge, which was over 75 years old at that time. The project had completed feasibility studies and a Detailed Project Report (DPR), but actual construction could only begin after receiving a no-objection certificate from the forest department. Officials had estimated that the bridge would be completed in 18–24 months. Local experts highlighted that this new road was necessary, especially with new routes being built from Oodlabari in Malbazar to Gangtok, which would strengthen the region’s infrastructure.

By 2025, the project received further momentum. The Central Government allocated ₹1,190 crore for the bridge, which will now stretch 6.85 km, including approach roads, connecting Sevoke to Ellenbari. The new bridge will serve as a modern route for heavy vehicles, reduce traffic congestion, and cut travel time across the river from 17 minutes to just 3 minutes.

Local activists have long demanded this bridge, but progress has been slow over the years. With the project now under the National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) after earlier delays in planning and land acquisition, authorities aim to complete it within approximately 36 months of starting construction. Once ready, the bridge will not only modernize transport in North Bengal but also strengthen the strategically important “Chicken Neck” corridor connecting mainland India to the Northeast.

Balancing Legacy and Modern Needs

The challenge now lies in balancing heritage conservation with modern infrastructure demands. While the new bridge will serve as a primary transport route, the Coronation Bridge is expected to be preserved as a heritage structure, with restricted use for light vehicles and tourism. Its restoration could involve structural strengthening, controlled traffic, and cultural promotion as a historic landmark of colonial-era engineering.

If successfully executed, this dual strategy would not only safeguard the 75-year-old Coronation Bridge but also ensure the region’s vital connectivity for decades to come. For the people of North Bengal, the bridge will continue to stand—not just as a passage across the Teesta, but as a living reminder of history, resilience, and architectural brilliance. Yet, time has taken its toll. Cracks, tremors, and rising traffic loads remind us that even marvels of the past have limits. With restoration plans underway and a new parallel bridge being constructed, the Coronation Bridge now stands at a crossroads between history and progress.

As North Bengal moves forward with modern infrastructure, the Coronation Bridge must be preserved as a heritage monument—a living relic of an era gone by, a silent witness to India’s colonial past, and a proud landmark that continues to inspire awe.

For generations to come, it will remain more than a bridge. It will be a testament to human vision and perseverance, a story etched in stone and steel, spanning the restless waters of the Teesta—a timeless guardian connecting the past, the present, and the future.